- The Lindy Newsletter

- Posts

- Moral Lag

Moral Lag

I was looking at the recent news about immigration and I thought about the concept of moral lag.

Our moral instincts are tools, evolved for specific conditions. When the world changes faster than our instincts update, they misfire.

This is moral lag

Consider hunger. Our deepest moral wiring shouts, Feed the starving. For almost all of human history, this was correct. Scarcity was the existential threat. You ate when food appeared, because it might not appear again. Our conscience was forged in that long emergency.

This explains the visceral outrage when Israel blocked food shipments to Gaza. For many, that provokes a deeper, more instinctive horror than the bombs being dropped on civilians. It triggers an ancient alarm, they are being starved. Support for the war in Gaza dropped fast after that moment.

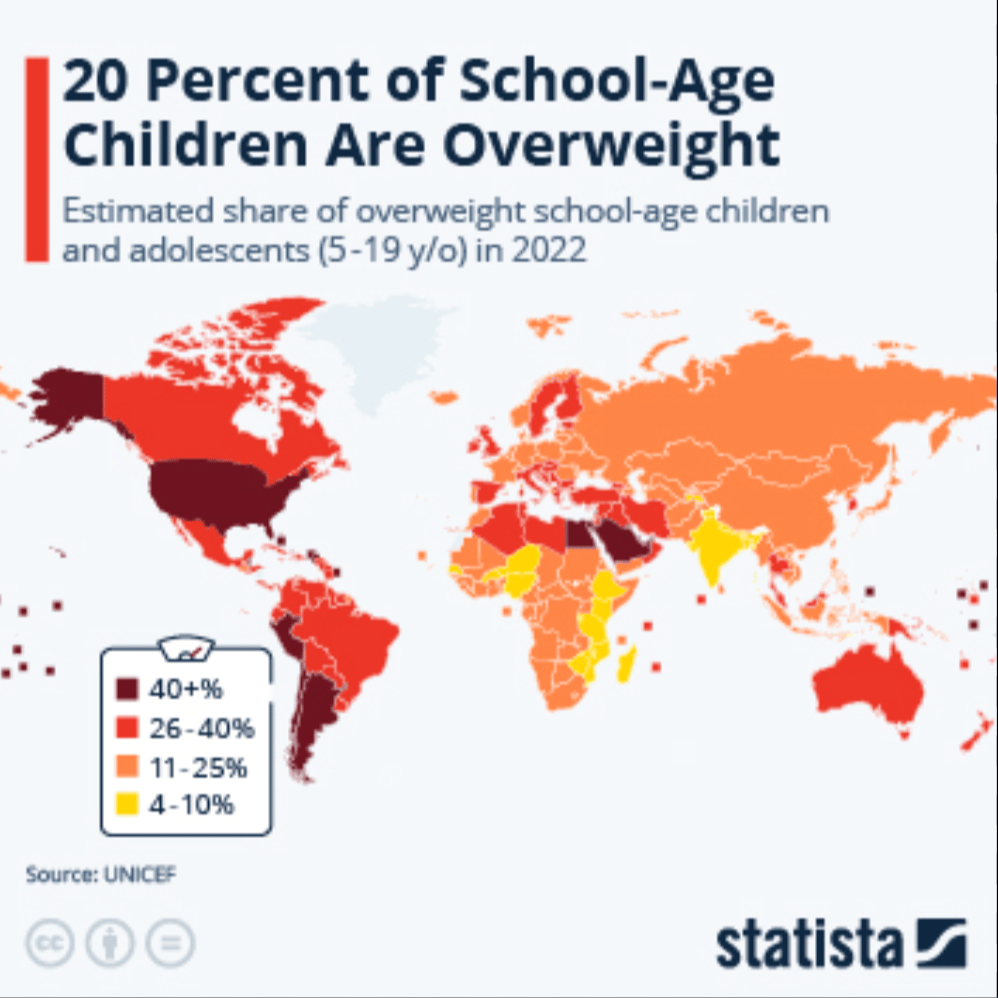

But that alarm is misfiring today. The world it was designed for is gone. The central nutritional problem for much of humanity is no longer scarcity. It’s abundance. Heart disease, diabetes, and metabolic collapse are now global epidemics. The poorer you are, the more likely you are to be obese. We are even developing drugs to stop people from eating themselves to death.

This lag profoundly distorts our view of social issues.

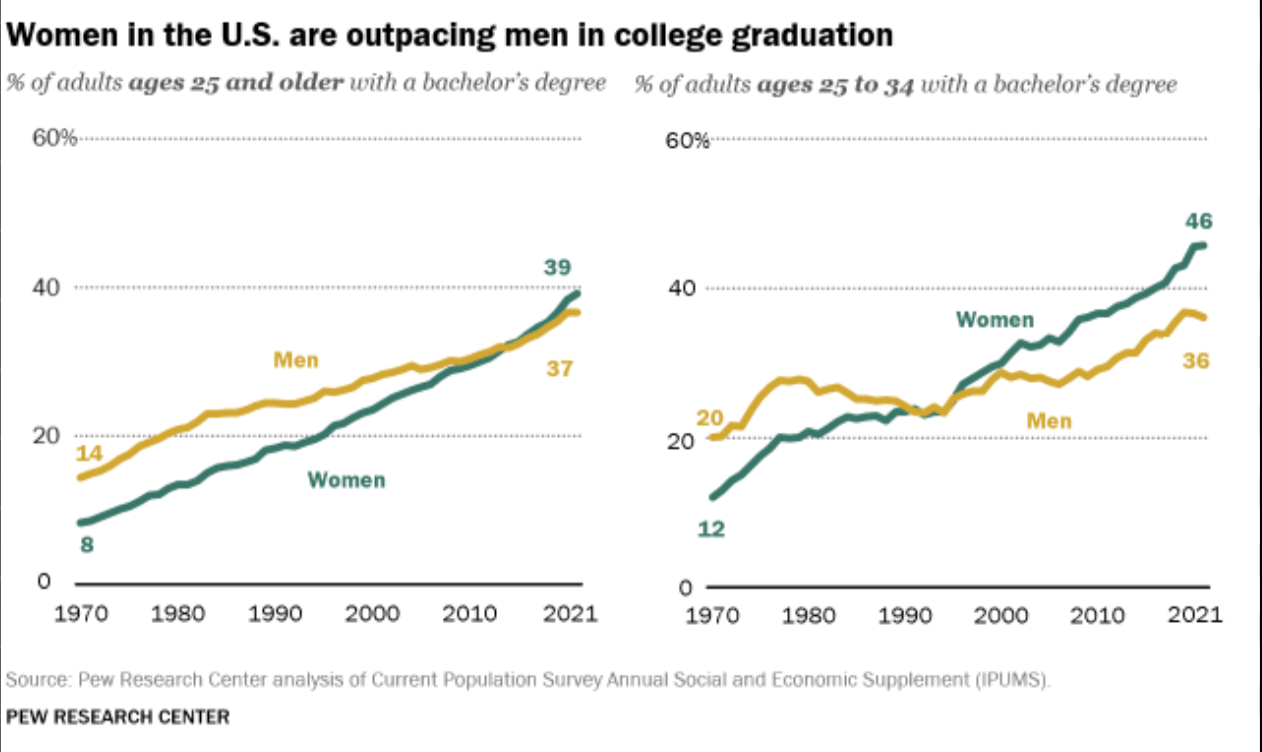

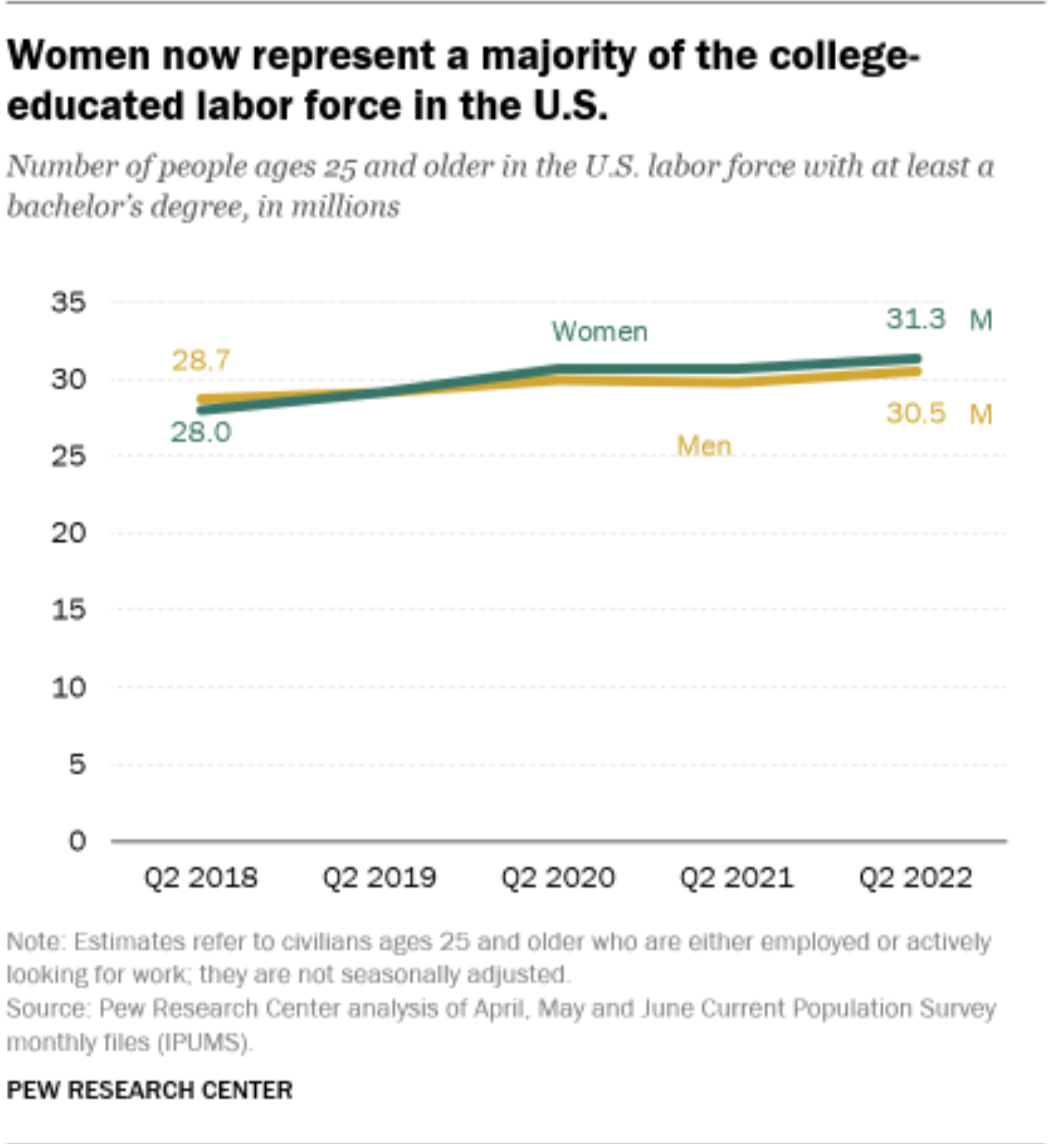

Consider the fight for women’s equality. The moral imperative of the late twentieth century was clear, break formal exclusion from education and work. That project largely succeeded. Girls now outperform boys across most educational metrics, and women are deeply embedded across the professional class.

Yet much of our rhetoric remains frozen in the era of closed doors, still framed as if access itself were the central problem. The moral language hasn’t updated to the modern trade-offs, dating dynamics, family formation, dual-earner norms, and the pressures of ubiquitous choice. We continue to fight the last battle, even as the terrain has shifted.

The same thing is happening with many social issues we are told about, we all have to pretend it’s still 1960 out there. It’s very silly.

But nowhere is this lag more consequential, and less examined, than in how America talks about immigration and deportation.

Deportations and the Frozen Moral Map

I don’t have a strong opinion on whether we should deport illegal immigrants or allow them to stay. Both are defensible policies with real trade offs. I see it as a political issue, not a fundamental moral one.

For many, however, it is a sacred moral cause. Protests erupt nationwide, sometimes turning deadly. This is a textbook example of moral lag. Many Americans viscerally see deportation as a death sentence because, for much of the twentieth century, that was often true.

Crossing a border then could separate survival from danger. Moving to the United States often meant escaping famine, repression, or economic dead ends. Deportation frequently meant returning someone to real peril. That is the frozen map in the American mind.

Today, however, removing a migrant from American usually triggers an economic change, not a death sentence. Our moral vocabulary hasn’t caught up, we still describe this as catastrophe.

American Exceptionalism

This moral panic over deportations is distinctly American. It stems from a specific, shared form of American exceptionalism.

Other nations enforce immigration rules as an administrative act, without existential drama. Japan deports thousands annually. Singapore enforces visa rules within weeks. China routinely deports people without issue. European countries remove people routinely. It’s just a standard governmental policy.

@theblackexjp How an honest mistake caused me to get deported from Japan. #blackinjapan #lifeinjapan #japan #tokyo #blacktravel #blacktravelfeed #blacks... See more

In the United States, however, deportation is rarely treated as administration. It is treated as moral catastrophe.

The left wing in America sees deportation as unconscionable because everywhere else must be terrible, violent, corrupt, hopeless.

The right wing sees America as this exceptional place that nowhere else in the world can compare to.

Both inherit the same twentieth-century American self-image, a unique safe harbor in a dangerous world. For the left, this makes us morally obligated to shelter. For the right, this makes us morally entitled to exclude. The disagreement is about generosity versus gatekeeping, but the underlying premise, that America is categorically different from everywhere else, is shared and unexamined.

But they’re both wrong, and the fastest way to cure yourself of this notion is to travel.

Traveling

One of the useful things I learned about traveling is how quickly it dissolves the notion of superiority.

I've spent time in South America, Europe, Asia. What strikes you abroad isn’t desperation, but ordinary life. Cities function. People work jobs, live in apartments, raise families. They have smartphones. Their kids go to school. They complain about traffic and rent. They navigate the same basic middle-class challenges, just with different constraints.

The American mindset has maintained a frozen mental map where deportation sends someone into the void, while the truth is the world is getting richer and more comfortable.

This isn’t to say America isn’t rich, it is. Americans own more stuff. If you want a large truck or a lottery-ticket chance at vast wealth, America is peerless. But the vast majority do not win that lottery, they live day-to-day lives of comparable quality to the global middle class.

A family in Medellín, Bucharest, or Hanoi lives in an apartment, sends kids to good schools, eats well, and is woven into a tight social fabric. They are not wealthy, but they are not suffering. Meanwhile, you need a high American salary to purchase the social stability and contentment that is often built-in elsewhere.

The label "developing country" is now wildly outdated. The infrastructure works. The food is good. What’s often surrendered is not safety or comfort, but American-scale consumption: the giant house, the second car, the endless stream of Amazon boxes.

Once you see deportation as a severe downgrade rather than a death sentence, a more unsettling question follows.

Is coming to the United States still the obvious, life-changing upgrade it’s assumed to be?

1) The Button Test. When I travel, I run a thought experiment, If a resident of X could push a button and immediately be given a working-class or middle-class life in the US, would they? Most people have a romanticized view of American life and don't fully think through what they'd be giving up.

2) Why Does Moral Lag Happen? The institutional, psychological, and social forces that keep us fighting the last war, not the current one.