- The Lindy Newsletter

- Posts

- Nature is Always a Give-and-Take

Nature is Always a Give-and-Take

I always like coming home for the holidays.

For one thing, it’s one of the few moments when people of every age occupy the same room, babies, teenagers, twenty-somethings, middle age, old age. Most of modern life today is spent in age segregated places.

Wealth and mobility allow people to optimize their environments with precision that was never possible before. Families move to suburbs, students to campuses, retiries to dedicated communities. The segregation is luxury, not necessity. Pre-modern societies didn't have the option, everyone shared space because they had to. We've chosen comfort over mixture.

When I’m home, I spend most of my time talking to my cousins in their early twenties. They’re the most honest people there. The conversations are better. They don’t edit much. They talk about what’s wrong. They talk about jobs they hate. Apartments they regret. Cities that didn’t turn out the way they imagined. Relationships that feel unstable. Or how things are going great.

Youth is honest like that. Children say whatever comes to mind. People in their early twenties still live close enough to childhood.

That phase doesn’t last though.

By thirty, the language shifts. By forty, it hardens. Life is “good.” Work is “busy.” Everything is “challenging in a good way.” Even when something is obviously wrong, it rarely gets named directly. Struggles are softened, edited, or skipped altogether. The raw honesty disappears.

No one is lying. Saying the truth just gets expensive.

My twenty-six-year-old cousin told me over dinner that she hates her job, thinks her boyfriend might be wrong for her, and feels lost in her new city. Meanwhile, my uncle, who I know is miserable at work and whose marriage is visibly strained, said his life was 'good' and 'busy.'

Saying your life isn’t working at forty is different. It doesn’t sound exploratory. It sounds destructive. It threatens everything at once, marriage, children, reputation, money, years already spent. You can’t just say it out loud and see what happens.

As you get older, your life stops being only yours. It starts holding other people up. You become something load-bearing or like infrastructure. You absorb doubt instead of sharing it. Certain things stay unsaid because saying them would make everything wobble.

People manage the story. They tell the cleaner version. They save the rest for someone they trust.

Older people are still interesting to talk to, often more interesting in other ways. They range more broadly. They’ve seen patterns repeat. They can talk about money, events, systems, history. They’ve accumulated understanding. The conversations deepen in some dimensions.

That’s the exchange.

Young people give you honesty without understanding.

Older people give you understanding without honesty.

You see this trade everywhere. It isn’t limited to age.

Trade-offs

Schopenhauer noticed it early. Intelligent people don’t get bored easily. They disappear into things. Books. Ideas. Problems. They sit alone for hours building elaborate inner worlds. Solitude doesn’t bother them. Their minds stay busy.

That depth comes with a cost. Focus makes interruption feel violent. Noise grates. Other people turn into friction. Obligations feel invasive. The same ability that protects them from boredom leaves them exposed to disruption. To pain. You can go deeply into a topic but you feel pain and annoyance more easily.

Cheerful people face the opposite problem. They need external stimulation, other people, movement, novelty. Boredom hits them harder. But they tolerate social chaos easily. Interruptions don't destabilize them. They can context-switch without suffering. What makes them vulnerable to monotony makes them resilient to disruption.

The Stoics noticed the same pattern at a larger scale. The higher fortune lifts you, the harder you fall. Success doesn’t just increase the pain of failure. It rewires what you’re vulnerable to. Wealth opens one channel. Status opens another. Reputation opens a third. Loss finds more places to enter. The peasant has little to lose. The king has everything.

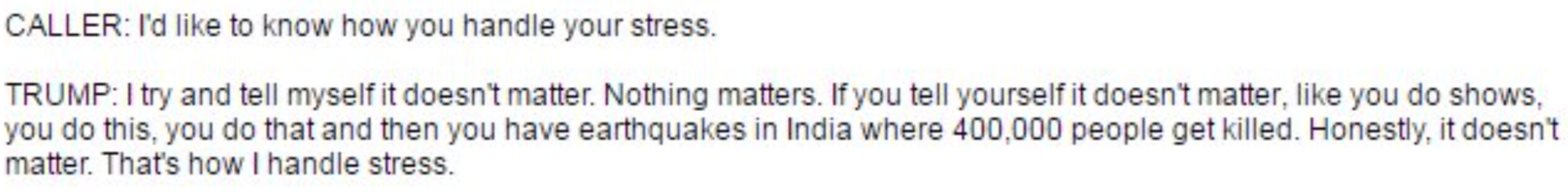

So they developed techniques to manage the exposure. They trained themselves to imagine worse outcomes in advance (premeditatio malorum), to adopt a cosmic perspective that placed personal setbacks against nature, time, and mass suffering, to de-center the self so private misfortune loses its exaggerated weight.

Most people already do a rough version of this without philosophy or training. During a bad stretch of life, they instinctively compare downward. They think about people who are worse off, sicker, poorer, buried under disasters or war. The comparison shrinks their own pain to a tolerable size. It isn’t noble, but it’s effective.

Trump shows the ugliest version of the move. When pressure builds, he jumps straight to catastrophe. Earthquakes. Mass death. History at its worst. The scale wipes out the personal. It’s crude, but the mechanism works. Make the frame big enough and pain loses leverage.

We're even now discovering trade-offs that were previously invisible.

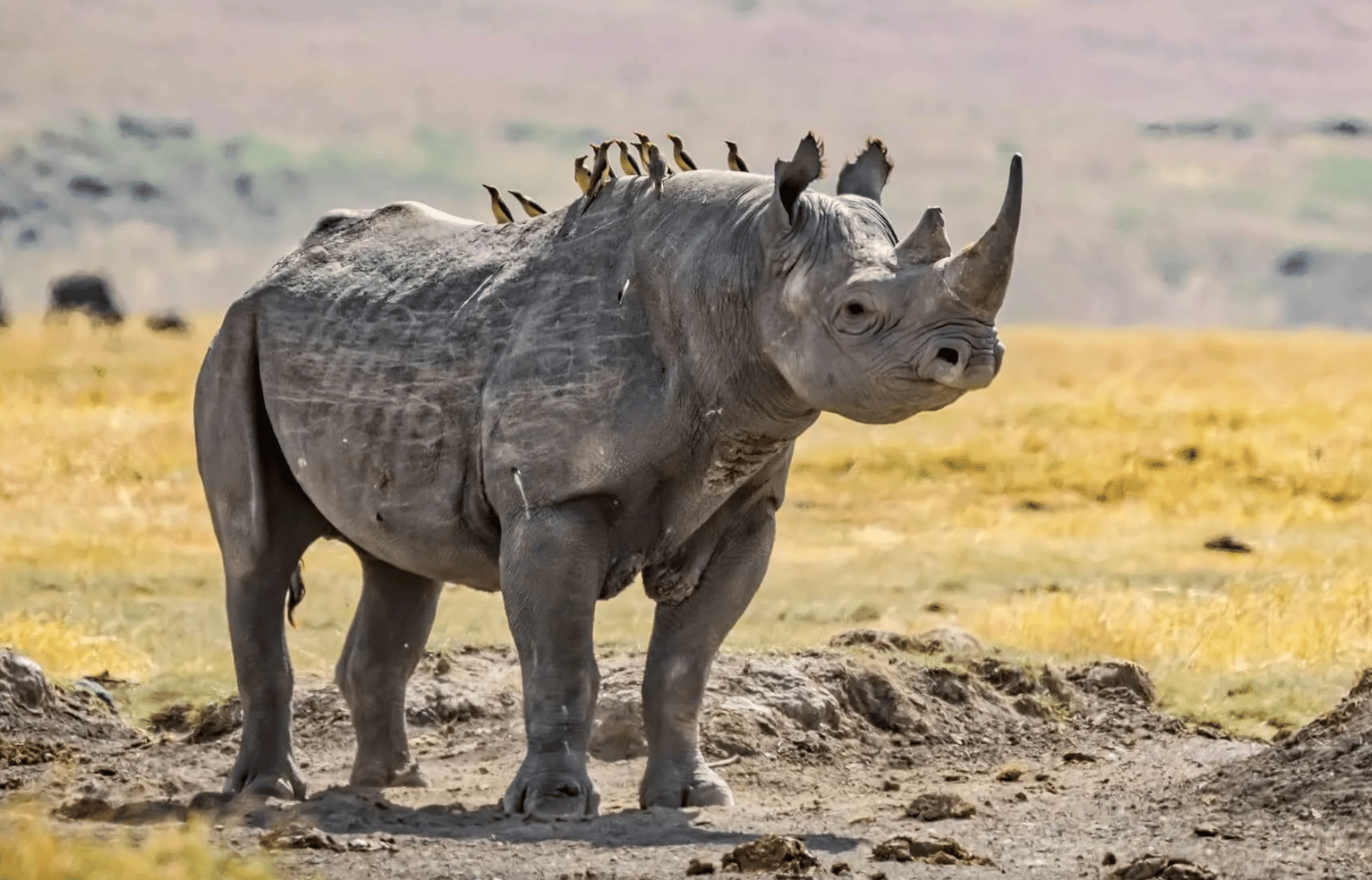

Nature doesn't offer free lunches. Even biology is a series of predatory loans. Take early puberty. For decades it looked like pure advantage, you mature ahead of your peers, you're bigger, stronger, more confident, sports come easier. Girls like you. But longer-term studies now show accelerated development means accelerated aging. You end up dying before someone who was a late bloomer. You might peak early, but you also decline early.

Awareness of trade-offs is not new. We've encoded it in our language: 'No free lunch.' 'You can't have your cake and eat it too.' Every culture warns that nature is give-and-take.

What we usually miss is that not all losses work the same way.

Manure turns into Fertilizer

Some are permanent exchanges. You trade honesty for stability, depth for social ease, fortune for peace of mind. What you gave up is gone.

But other losses convert. Manure is waste to the organism that produces it, but fertilizer to the soil that absorbs it. What looks like pure loss at one level becomes productive at another.

Take selfishness. In isolation, it's an ugly trait. The person who takes without giving, the person nobody wants to sit next to. It ruins dinners. It corrodes relationships. It exhausts everyone in the room. Put the same person inside the right economic structure and something else happens.

They want money. They start a business. They hire people. They compete.

They don't stop being selfish. The trait just changes form. Jobs appear. Products appear. Money spreads outward. The vice stays intact. The output changes.

The 17th century writer Bernard Mandeville said this out loud three centuries ago

He argued that private vices generate public benefits. The idea sounded obscene. But he was describing a mechanism, not making a moral case.

He suggested that a society of pure virtue might not be wealthy at all. If everyone were perfectly content, patient, and selfless, what would drive economic activity? Contentment doesn't generate demand for new products. Patience doesn't create urgency to build or innovate. Selflessness doesn't fuel the ambition that starts enterprises. The dissatisfaction we try to cure individually might be what keeps the economy running collectively.

Maybe this is what religious teachings gesture toward when they emphasize poverty over riches, when they warn about wealth as a spiritual danger. Not because poverty is virtuous in itself, but because the economic system that generates wealth requires vices as input.

This doesn't mean we should celebrate vices or pretend they aren't corrosive at the individual level. A society that actively cultivates selfishness, anger, and envy would be unbearable to live in. The vices work despite being vices, not because they're secretly virtues. It would be like worshipping manure.

But that raises the obvious question: if vices can generate benefits, why doesn't it happen everywhere? Why do some societies turn greed into prosperity while others just get corruption?